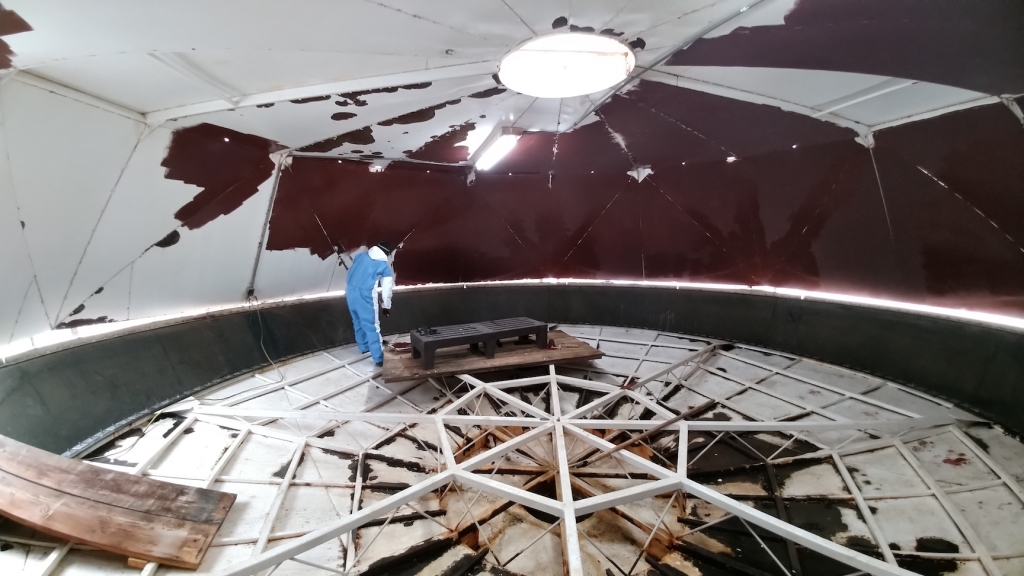

TM to Crew Quarters hatch design

SAM volunteer Colleen Cooley and Kai Staats worked on the design of the portal between the Test Module and the Crew Quarters, determining how crew members will move between the two distinct section of the SAM habitat. While it was the original intent to cut down into the knee-wall of the Test Module to create a walk-through, it was determined that by instead keeping the hatch at a higher level, it could be contained entirely in the space defined by the current window frame which is being replaced by a single sheet of steel. As such, the hatch can be closed to return the Test Module to a fully pressurized, hermetic seal and operate as such with or without the adjacent crew quarters sealed. This gives SAM a greater degree of flexibility and maintains the integrity of the historic Test Module while giving visiting teams a true sense of moving from one module into the other much as one does in the International Space Station.