SAM offers a unique, highly engaging experience for visiting crews as it likely the first time they have monitored carbon dioxide (CO2), relative humidity (RH), temperature (temp), VOCs, and pressure in a hermetically sealed vessel for the duration of an analog mission.

While prior discussions of air quality in SAM usually focus on CO2, the APUS ARG-1S crew was asked to also keep a close watch on relative humidity as they are the second crew to condense the moisture contained in the vessel’s body of air, filter it, and then add it back into their potable water supply.

There are a total of seven devices able to condense water vapor into liquid water within SAM: 2 mini-split heat pumps and 2 dehumidifiers in the Test Module; 1 mini-split and 1 dehumidifier in the Engineering Bay, and 1 mini-split in the Crew Quarters. As the TM currently contains two racks active in hydroponics to provide fresh vegetables for the crew, the mini-splits must remain set to Heat, even in this too-warm winter in order to maintain an approximation of the ideal growing temperatures. In heating mode, any condensation occurs on the condenser, outside of SAM.

The dehumidifiers can be set to presets of Continuous, 55%, or 45% with manual setting of a much wider range. They activate when they sense the relative humidity to be at or above the given threshold. The mini-splits condense water at the air handler inside the habitat, or can be set to Dehumidify in which they neither heat nor cool the habitat, but work instead to capture water from the air and drain it into a potable bucket, one below each wall-mounted unit.

As such, the crew may elect to set the mini-splits to Heat, Cool, or Dehumidify as they see fit in the Engineering Bay and Crew Quarters, manually changing the settings throughout the day and night. The crew has access to a local, real-time display of the SIMOC Live data via the dedicated terminal in the EB, or on any of their laptops.

At the SAM Operations Center and Mission Control, which for this mission was occupied by two dedicated officers and the rotating crew before and after the crew switch on day 5 (through the airlock), the same data is also available, delayed by 20 minutes to simulate the light-travel time from Mars to Earth.

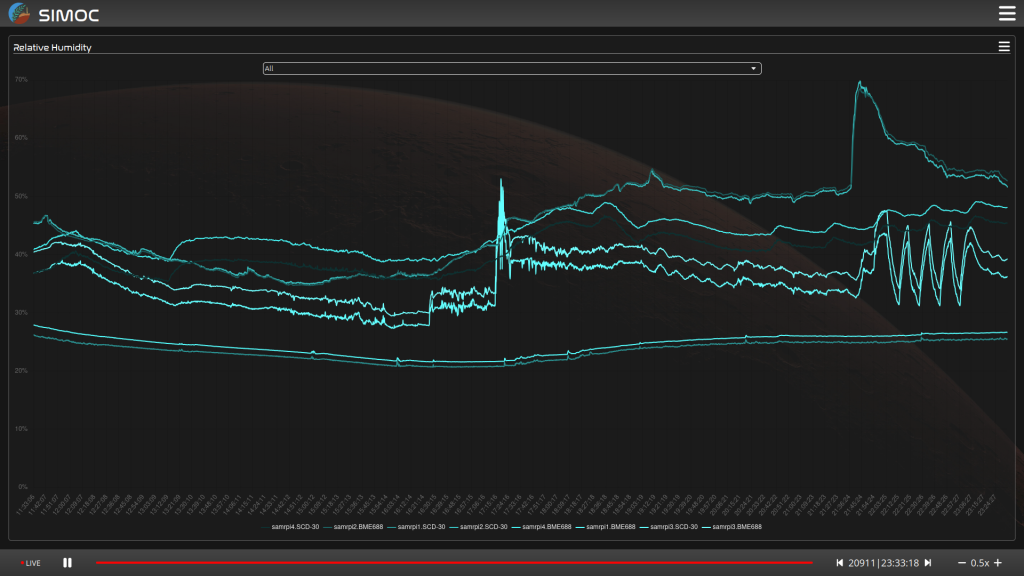

One of the functions of Mission Control is to monitor the air quality, at all times, and to guide the crew as to how to manage the components. So, when a regular oscillation of humidity followed a certain spike, as registered in both the EB and CQ, it invoked a discussion at Mission Control and dialog (delayed by 40 minutes round-trip) with the crew.

Is this a false reading? And if not,

What is causing the spike in humidity?

What is bringing it back down again?

Is this a false reading? Given the data visualization on the SIMOC Live dashboard, there was some concern for the spikes and valleys. However, as RH and temperature are included with both the SDC CO2 and BME pressure sensors, there are two RH and temp sensors on-board each SIMOC Live board, and one board in each of the four modules. This is important when analyzing any of the data streams, for it helps to immediately determine if a short-term fluctuation is in fact a representation of the real world, or an anomaly in that particular sensor and data stream. It was confirmed that this is a real reading as a total of four sensors (2 in EB, 2 in CQ) were matched in the pattern.

What is causing the spike in humidity? The first guess was boiling water for coffee or tea, cooking, or exercise. But intuitively the spike was too large, registering in both the EB and CQ. In fact, it appeared that the humidity was propagating upstream, meaning against the flow of air from the Air Intake Room (SAM AIR) to the TM, EB, and CQ. As such, this had to be a good bit of moisture released all at once.

If not cooking or human respiration, then what? We then asked the crew if they had switched the mini-split units from Dehumidify to Heat, as this would disable the function of condensing moisture and quite possibly dump moisture into the air. The theory (proposed by Kai) was that the heat exchangers have a large copper surface area by which a relatively large volume of air can interact, thereby heating, cooling, and/or removing moisture. If that surface area is wet with condensate, and the mode is switched to Heat, the coils will rapidly move from cold to hot and immediately eject the water molecules back into the air as soon as the fans spin up.

We inquired if in fact the crew has made this switch, and yes, they confirmed this to be true.

What is bringing it back down again? The oscillation then is the dehumidifier in the same module working to reduce the humidity, turning off when it reaches its desired low threshold, then kicking in again as the humidity rises.

Case solved!